Where the Wading Birds Live

This is Part 1 of a two-part series examining Florida's wading birds, from their near extinction and eventual recovery to a future unknown.

I have an interesting piece of Florida history to share with you; let’s see if you’ve heard about this before.

Prior to the Florida land boom in the 1920s, the state remained an agricultural and rural hub. Suburbia and busy city sprawls were virtually nonexistent and resources from both land and water remained vast and largely unvarnished. But sometime around the late 1800s, Florida became a favored destination for tourists to enjoy its natural beauty and climate.

Around the same time, Florida also became a popular place for potential investors looking to capitalize on new and rapidly growing industries such as sponge harvesting and phosphate mining. As a result, flourishing economic conditions spurred the state’s transportation and hospitality industry into overdrive. With railroads, city and county roads, hotels, and small towns on the horizon, and as newcomers to the state began their inevitable journey through coastlines, swamps, grassy waters, and forests, Florida was on the cusp of ingenuity, innovation, and unfortunately, doomed for exploitation.

The Everglades, one of the world’s largest subtropical wetlands, once covered more than 2 million acres across South Florida. The swampy region was (and still is) home to reptiles, fish, panthers, hundreds of bird species, and much more. But attempts to drain the Everglades for agriculture and development would prove moderately successful, and around the turn of the 20th Century, Florida’s wild landscape began to shift.

And all the while, as industrialists and state legislators appealed for a drained and dryer Florida, another threat loomed in the wetlands. This time, it was the plume hunters.

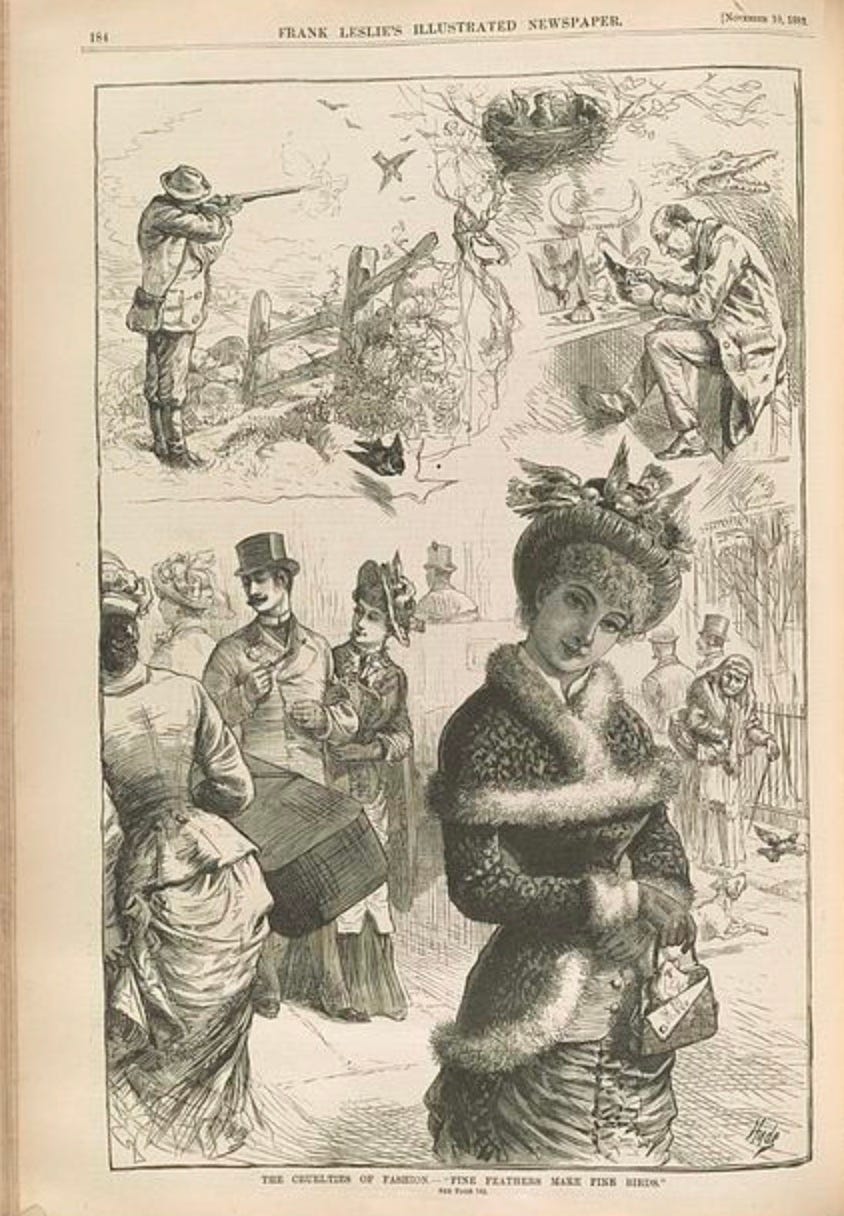

The high cost of a feather

Most any fashionable and high society woman in the late 1800s wore a hat. These hats were adorned with feathers of all shapes, sizes and colors ranging from shades of pinks, blues, blacks, browns, and of course, the most vibrant of whites. The Great Blue Heron, Roseate Spoonbill and flamingos were all hunted for their plumes. But because colored feathers faded over time, it was the brilliant white feathers that many women wanted. White ibis, Cattle Egrets, Snowy Egrets, and Great Egrets all fetched a high price in the plume trade. In some cases, the white feathers of egrets, and specifically Snowy Egrets, were worth more than diamonds or gold.

Plume hunters and gunners in Florida were a notoriously rough, albeit ignorant, bunch. According to Death in the Everglades: The Murder of Guy Bradley, they were a mix of settlers and hunters from the southern part of the state and up and down the Gulf Coast. Many were poor and arguably unaware of the environmental impacts of killing birds in such large numbers. They were, quite simply, getting their ‘cut of the action.’ But the big players, or rather, the plume tycoons were often out of state and wealthy business owners, such as Mr. J.H. Batty, who owned a highly profitable taxidermy business out of New York City.

Estimates place the number of wading birds killed during that time at approximately five million. Island sanctuaries, rookeries, and parts of the Everglades —where egrets, ibis, spoonbills, and herons once nested peacefully — lay completely gutted. Entire bird families were wiped out, all at once, shot to death and scalped, with a bloody mess of bodies left behind. A devastating sight, to be sure. But for ten dollars per plume, the death and destruction was worth it in the eyes of hunters and the fashion industrialists who led the way.

In the year 1900, the Florida Audubon Society was created and the state’s first bird protection act was passed in 1901. Killing birds in Florida for the sale of their plumes was now a criminal offense, though enforcement proved challenging in Florida’s wet and wild landscape. A former plume hunter, Mr. Guy M. Bradley, had been hired by the Audubon campaign as a game warden to monitor the coast of South Florida, and over time, his work paid off: wading bird populations increased. But on July 8, 1905, Bradley was murdered by a gang of plume hunters who just couldn’t give up the hunt.

Since then, several state laws and federal efforts have put the plume hunting business to rest. Many of the wading birds continued to rebound, thanks in part to the efforts of national and state conservationists who worked to end the trade, advocating for new laws and protections. And, yet, wading birds in Florida are living with a different type of threat, and one that is equally as devastating: habitat destruction.

The rich, life-giving resources of Florida begin in the wetlands. For wading birds, this is where they breed, live and nest—finding solace on rookeries and hunting fish, amphibians, reptiles, and crustaceans in which to feed themselves and their young. By appearances alone, these low-lying, marshy areas seem hearty and robust; able to thwart deterioration from major weather events or even drought. But Florida’s wetlands, including, but not limited to, the Everglades, are hardly invincible—and drainage attempts have proven just how fragile the environment can be.

Coordinated efforts to drain Florida’s wetlands extend back to the turn of the 20th Century. And there’s a reason for that: a steep population increase and the desire for ‘new’ and dryer land. As mentioned previously, the sunshine state experienced rapid growth as real estate, railroads and highways expanded up and down the west and east coast and throughout low-lying areas in Central Florida. But flooding remained an issue, which is why the Army Corps built a large dyke around Lake Okeechobee in addition to pump stations, levees and over 1,000 miles of canals in and around Florida’s wetlands.

So even as bird populations rebounded after the plume trade, wetland drainage projects caused wading bird numbers to fall dramatically—once again. The need for dryer land and space for suburban sprawls, commercial real estate, agriculture, and even ecotourism was worth the environmental costs, for a little while, at least.

Coming soon! Please be on the lookout for Part 2 of this two-part series about Florida’s wading birds which will expand more on habitat destruction and overdevelopment.

wonderful Lara. great background on such a vibrant state. thanks