What's Done is Done at Dudley Farm

In 1859, Philip Benjamin Harvey Dudley and his wife Mary built Dudley Farm in Newberry, Florida. But like other settlers involved in cotton production, they didn't build it alone.

The city of Newberry, an area of North Florida that borders between Archer, Jonesville and Gainesville, is home to a once prosperous farm and community center named Dudley Farm. It turns out that the farm, now designated as the Dudley Farm Historic Sate Park, has a long and at times turbulent history.

Last month, we visited Dudley Farm with very little background into its historical value or symbolism in this part of Florida. We understood it to be a working farm, with a few animals on site, that allowed for visitors. But, in reality, the farm is more than that—much more.

Located off Newberry Road, just west of Gainesville, the site sits secluded, surrounded by large oak trees, sabal palms, citrus and dogwood trees and cattle pastures, and currently spanning 325 acres (originally, the farm was 640 acres) previously operated by the Dudley family for three generations. It was sold to the state of Florida in 1986.

Though several structures on site have been restored, each remain in their overall original state. Nothing has been recreated; nothing has been removed. The main living house was rebuilt in 1881 by Dudley Jr.

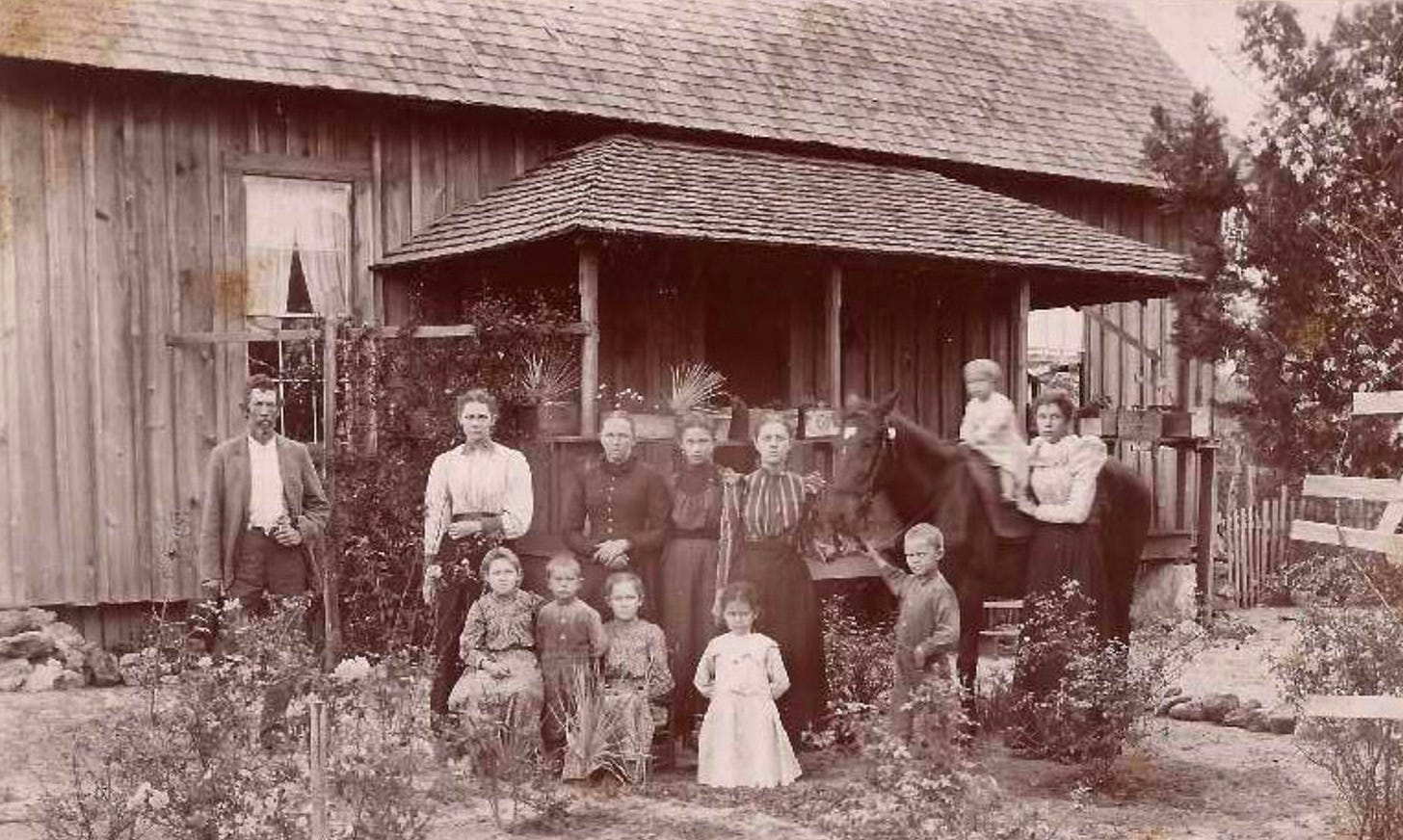

But it was settlers Philip Benjamin Harvey Dudley Sr. and his wife, Mary, that started the original farm, along with 30 African American slaves.

For context, of the almost one-third of all Southern families who owned slaves, 88 percent owned fewer than 20, while approximately one percent of families owned more. Dudley Sr., therefore, quickly became a middle-class agrarian through his ownership of enslaved people who cleared land and grew cotton at the Newberry farm.

At the time, around 25 years leading up to the Civil War, most Florida slave owners were transplants from Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, searching for new and fertile land, settling in and around Tallahassee and included Gadsden, Leon, Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton counties — then expanding into Alachua and Marion counties. This was known as “Middle Florida.”

Dudley Sr. and his wife moved from South Carolina to Newberry in 1852 and purchased the land that became Dudley Farm in 1859, just two years before the start of the Civil War.

Florida was a fractured state when it came to the Civil War and institution of slavery. When members of the state legislator, most of whom were powerful Middle Florida planters and slaveholders, voted to secede from the Union, a large number of Floridians to the East and to the West pledged loyalty to the United States, resulting in Union military disruptions along the coastal counties. According to Florida Humanities, this is where men, women and children escaped to when seeking freedom in Florida.

Given Dudley Sr.’s history, ideology and position as a slaveowner, he joined the Confederate Army as a captain of the Alachua Rangers 7th Regiment, leaving the farmhouse and land behind. However, Middle Florida, which included the Dudley Farm, was protected from Union forces due to geographically separated war zones. As a result, the Dudley family and their property remained unscathed.

After a few years, and when the war had ended, Dudley Sr. returned to the farm and the humans he enslaved (as well as others enslaved in Middle Florida) were now free men, women and children.

Post Civil War in the South included triumphs and many significant challenges for African Americans and the farms they once lived and worked on, including the Dudley farm, where Dudley Sr. and his son turned to grazing cattle, while also raising cotton and other crops with hired help. Payment often came in the form of "furnish" which consisted of pork and sugarcane.

In time, however, and despite changes to daily operations and federal law, Dudley Farm became a focal point for the larger Archer region and a type of community center for cattlemen, townsfolk, and other merchants in the area over the course of 100 plus years. This includes through the Great Depression, changes in agricultural norms and mechanization in addition to the deaths of managing family members such as Dudley Sr., Dudley Jr. (Ben), Fannie (Ben’s wife) and their three sons.

The last Dudley to remain on the farm was Miss Myrtle Dudley, where she lived until her death in 1996 at the age of 94. Carrying out the wishes of her mother, she kept the farm intact by donating 24 acres to the park service in 1983, then sold the remaining 232 acres to the state. In January of 2021, Dudley Farm Historic State Park was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

According to the Florida State Parks website, interviews were recorded providing details about daily life on the farm and changes over time. I was able to locate one interview online between Myrtle Dudley and Lisa Heard, conducted February 25, 1992. At 60 pages long, the interview is quite extensive, though at times meandering, giving historians and writers a better and more intimate view about what happened on the farm and what happened to some of the slaves who were freed from captivity. It’s a lot to unpack. If you’d like to read it, here is the link.

After first visiting the site and later searching for more information through articles and library databases, Dudley Farm Historic State Park seems to be a physical manifestation of deep-rooted memories. In other words, there are stories untold that’ll most likely stay that way, locked away with those now deceased.

Yet, Miss Myrtle did attempt to tell her side of the story in the recorded interview. One topic that often came up was that of the Newberry Six. Her story, told through the lens of time and emotional recollections, does line up with other versions. She does, however, hint at ongoing hostile relations with the local Black community, many of whom were previous slaves in the area. This likely played a role in the escalation of events on Friday, Aug. 18, 1916.

After reports of a hog stealing ring were made to Newberry law enforcement, Deputy Sheriff George Wynne, younger brother of Fannie Wynne Dudley, visited the home of Jim Dennis, one of the suspect in the case, at 2 AM. Another suspect, Boisey Long, was in the home at the time, and shot Sheriff George, killing him soon after. Both Dennis and Long were black men.

In response to the sheriff’s death, Miss Myrtle recalls in her interview how a mob of townsfolk were in ‘such a tantrum’ and that ‘they did not look natural.’ Then came the lynchings. It was reported that Jim Dennis was shot to death by the angry mob, and his siblings Mary Dennis and Bert Dennis, family friends Andrew McHenry and the Reverend Josh J. Baskins, and Jim’s sister-in-law, Stella Young—all found to be innocent after the fact—were hung from one large oak tree near Newberry’s town center.

While some writers speculate that members of the Dudley family participated in the lynchings to avenge the death of their beloved Uncle George, there is no definitive proof. But there is an indisputable connection between the Dudley Family and the Newberry Six discovered through Myrtle Dudley’s interview.

And so my visit to Dudley Farm Historic State Park was, by all admission, mystifying. The site itself was pleasant; beautiful old Florida flora and historic structures in their authentic form. Flowers bloomed, butterflies danced through the farmhouse garden, cows grazed on green pastures. But there was a stillness there, as though time itself had abruptly stopped and intrinsic memories deep within the land and buildings lived on. It’s not an easy feeling to describe.

If I had to sum up Dudley Farm knowing what I know now, I’d describe it as a blend of eerie and paradoxical. To what extent should the historical relevance focus on the Dudley estate as a long-standing working farm and community center versus a place where enslavement and oppression took place?

Perhaps a better balance will be achieved, but that’s not for me to decide.